When music requires her to cry, Japanese traditional dancer Naoko Kihara barely alters her expression. It’s her arms and torso that moves like a slow-motion wave.

“Expression is minimal because we cry with our body,” said Kihara, wrapped in her white and navy kimono, on a recent day at her dancing studio in Mexico, where an estimated 76,000 Japanese descendants live.

“It is the dance that is speaking, interpreting, since we do not smile, shout or laugh.”

Kihara won’t reveal her age, but she’s been practising Japanese traditional dance for almost 24 years. Born in Brazil to Japanese parents who later moved to Mexico City, she carries on the legacy of Tamiko Kawabe, her mentor and pioneer of Hanayagi-style dance in the country.

For Latin American audiences, Kihara said, Japanese traditional dance might be hard to embrace.

Unlike the fast-moving interpreters of samba and salsa — widespread in Brazil and Mexico — Hanayagi dancers move quietly and gently, performing just a few moves that their bodies keep fully controlled.

“Is this yoga?” a spectator once asked Kihara, who responded: “No, it’s an interpretation.”

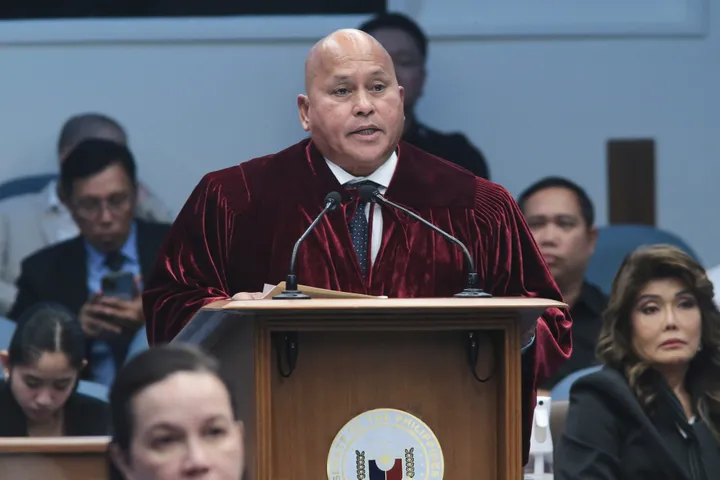

Naoko Kihara

Some of her repertoires are almost sacred. Japanese dances such as Hanayagi and Kabuki have been historically performed to honour the emperor, considered arepresentativeofgodintheShintoreligion.

For traditional dancers, choreography is a sign of respect and no detail is minor. How a woman holds her fan speaks of her sense of elegance and honour.

“You are not taught a dance, but a way of living,” said Aimi Kawasaki, a 21-year-old student of Kihara who will soon travel to Tokyo hoping to receive her dancing diploma.

Born in Mexico after her parents moved from Japan, Kawasaki says that Hanayagi is like ballet, but with an important exception: While Japanese traditional dancers are delicate and elegant, they never stand on the tip of their toes or pull their bodies toward the sky.

“A Japanese dancer is rather crouched,” Kawasaki said, her teacher demonstrating the posture: firm torso, bent knees and feet close together, as if she were a flower rooted to the ground.

“It’s to be humble,” Kawasaki said, and because Japanese traditional dance maintains profound codes.

“We move our bodies close to the earth because we are part of nature,” Kihara said. “It is a respect for the earth.”

In the Japanese worldview, Kihara said, the dance originated from earth, air, fire, and water. “That's our essence; it's our basis.”

Naoko Kihara

To keep this in mind, each Hanayagi dancer takes an oath when receiving her diploma in Japan. It’s like a manual of honour, Kihara said. A promise to preserve one's legacy.

Thirteen students — seven of them at the basic level — study in Ginreikai, her dancing studio.

“In our performances, it’s all about patience,” Kihara said. “We call them ‘long songs,’ because they are not plays with a beginning nor an end.”

Eiko Moriya, another descendant of Japanese migrants who will soon travel to Tokyo to get certified, has spent the last three years perfecting the long songs she’ll perform before the Hanayagi committee.

Her mentor watches her attentively while Moriya’s feet slide delicately over the wood floor, and always provides feedback. “Move your foot only when the music asks for it. Be mindful of the rhythm. Don’t overbend your arm.”

“Dancing is a transformation,” Moriya said. “Our dances are pieces of culture that are re-signified.”

Naoko Kihara

The meaning of their performances is conveyed through music and movement, Kihara said. Even in front of foreign audiences who might not understand a Japanese song, their bodies are their means to speak.

Her favourite long song, a story about unrequited love, portrays a princess convinced that the man she loves has transformed into the bell of the local temple. So, to get to him, she turns into a snake.

“There are just a few movements, but each of them portrays her belief of transforming,” Kihara said. “It is a story about anger, courage. It symbolizes the suffering of humanity.”

The songs that she and her colleagues perform for Mexican audiences are shorter and less complex than th e original Japanese long songs — a dance can last up to five minutes instead of 20 or 30 — but creating new choreographies and adaptations for foreign scenarios does not diminish her excitement.

“Through Japanese dance, we connect,” she said. “It is an exchange of cultures.”

“Ginrekai,” which translates into “silver mountain,” was the name chosen by her predecessor for the school because she believed that Japan and Mexico share more than their sacred volcanoes. If Mount Fuji and Popocatépetl are so similar, she used to say, it’s because deep down we are all the same.

“At Ginrekai we have that cosmic vision,” Kihara said. “Humanity is divided by religion, by culture, but for me, dancing is a way of saying: We are all one.”